By Jason Wojciechowski on January 2, 2014 at 11:05 PM

Hey Jason, where've you been? Co-editing Baseball Prospectus 2014, mainly, which was a blast but which took up a lot of time. You can preorder for, at this writing, $16.35, which strikes me as absurdly cheap given the huge word count of (I will attest, immodestly) great content. Anyway, that's where I've been, but I'm back now.

There are apparently 55 days until the first spring training games will be played, which means less than that until everyone is in camp and even less than that until pitchers and catchers (so many catchers) and coaches will be there and even less than that until baseball will rumble to life in anticipation of pitchers and catchers (so, so many catchers) reporting. That rumbling will be happening before we know it. It's nearly upon us.

Which is exciting! But which also means that it's time to get to work. Billy Beane is never done, but Billy Beane is probably mostly done. Which means we can look at the roster and figure out exactly what we've got to root for this year, where we're headed. I haven't been successful in the past with these sorts of systematic longish-term series, but I'm going to try again. A player a (more or less) day, some stats, some memories, some predictions, some insights. Some music.

Playing right now as I start this post: A Tribe Called Quest, "Public Enemy."

Coco Crisp had his $7.5 million option exercised a few months back, as no-brainer as a $7.5 million decision ever gets for Billy Beane. He won't be the A's highest-paid player (Yoenis Cespedes and Scott Kazmir are guaranteed more; Jim Johnson will get more in an arbitration-avoiding contract), but there's a good chance that his contract winds up representing more than 10 percent of the team's major-league payroll.

In the larger major-league context, where teams paying something like $5 or $6 million per position-player win (or really per non-reliever win), Crisp is very likely to be a steal—despite not playing more than 136 games in any of the last four seasons, he's averaged 3.1 WARP, 2.9 fWAR and 3.3 bWAR per year, with the variation coming, as you'd expect, from defense: UZR only likes Crisp to the tune of +2.6 runs over those seasons while FRAA and DRS are at about +15. Based on two of three defensive systems, including my favored one for a variety of reasons you either already know about or do not care about, and the eye test (and yes, taking into account his pitiful arm, the negative effects of which he attempts to minimize with a very quick release), Crisp has looked above-average in his time with the A's, even as he progresses inexorably into his 30s.

Fitting with that defense, Crisp has been an asset on the bases as well. The 141 steals in 162 attempts (87 percent, well above any reasonable measurement of the break-even level) are the most visible expression of his speed and baserunning smarts, but nobody racks up +17 (BRR) or +26 (BsR) runs on the bases over four years solely by stealing. Crisp takes extra bases with regularity, and while the four runs a year he's adding (say, using the more conservative BRR estimate) don't sound like much, put them in context of how much they'd cost a team on the free-agent market (call it $2.5 million) and you get a sense for just how not-nothing it really is. A grand don't come for free; neither do runs.

At the plate, Crisp had a career year in 2014, posting his highest TAv, barely nudging 2010's .293 by two points, and his highest total batting runs (by BP's metrics), beating his prior career high (2005) by three runs. He's 34. He's not doing that again. But in his worst year with the A's, he TAv'd .261, which is by definition one point above the league average, and which bested that year's major-league center field positional average by that same one point. That's a lot of numbers when I could have just said that Crisp has been average at worst at the plate with the A's when you take into account proper weighting of offensive components (which shouldn't be controversial) and park factors (which might be, though Crisp's lowest personal park factor with the A's was 94, i.e. he's only getting credit for hitting in parks 6 percent below average in scoring, a big number but not an absurd number).

What this adds up to is Steamer projecting a 3 WAR per 600 PA pace, and while Crisp is as much a lock as anyone in the league not to come to the plate 600 times, that's still an above-average player and one the A's can afford to lose for a brief period, what with Craig Gentry and Yoenis Cespedes and Josh Reddick, one of whom is a flat-out center fielder, one of whom might kinda be a center fielder and one of whom can cover the spot in a pinch without embarrassing himself, all on the roster. (ZiPS and PECOTA haven't yet been released publicly. Oliver is out but is doing hilarious things right now on FanGraphs, namely predicting 286 games, 1200 PA and 11.4 WAR for Crisp next year. (It's not just Crisp.))

Whether Crisp can repeat his 2013, or approximate it, gets into that mishmash of indicators we like to look at without admitting to ourselves that we're just talking nonsense and dreams. BABIP? .258 in 2013. Walk rate? Career high. Strikeouts? Career low despite the league exploding in whiffs around him. HR/FB? Career high.

I don't know. I'm bored already with this. I probably won't talk about it again.

Whatever Crisp used to be or whatever Crisp has been reputed to be, what Crisp is now is a guy who ranked 114th out of 140 qualifiers in swing rate despite ranking in the top quartile in zone percentage (which makes sense because who fears Coco Crisp? Sure, he slugged .444 in good pitchers parks, but ... who fears Coco Crisp?) and 18th (lowest) in whiffs per swing, fueled in part by a 10th-best chase percentage sandwiched in between those of Jose Bautista and Ben Zobrist. When you watch Crisp at the plate, are these numbers you expect? Maybe it's his twitchiness, maybe it's his size, maybe it's his speed, maybe it's his .330 career OBP. Whatever it is, I, at least, think of Crisp as a bit of a hacker, a guy who'll expand the zone a little to get his pitch when he's better off spitting on the pitch and taking a walk, but he's not really that guy, at least not now, or at least not in 2014, if he ever was.

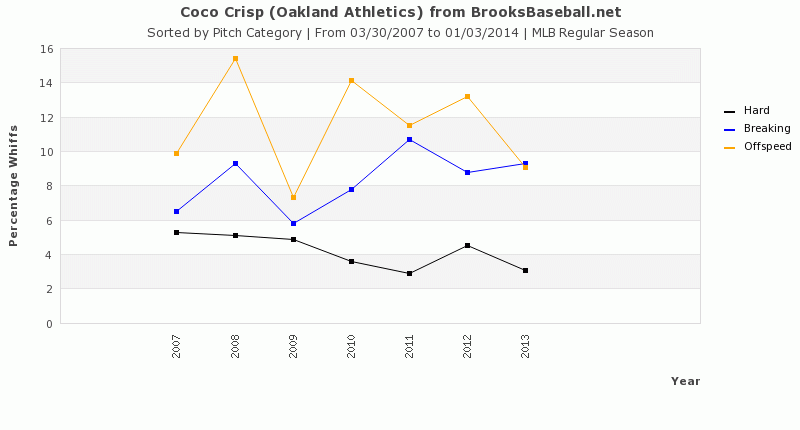

You could spend all year on Brooks Baseball, but this graph jumps out:

I don't, to be honest, know what the measure is. I can't seem to figure out how strike zone discrimination is measured, what it's measured against and so forth. Whatever it is, assuming there's some validity underneath it (and given the minds behind the site, I'm willing to bet there is more than I normally might be), what we see jumping out, after a more gradual increase through his career, is Crisp's understanding of what off-speed pitches are doing. His approach on this pitches, if anything, per another graph on the Brooks site, has actually gotten slightly more aggressive, which is one of those good signs—he's swinging at the curves and changeups he's supposed to be swinging at.

I'm not a scout and I didn't watch Crisp in 2005, but these signs are the ones you look for as a player gets older—physical tools degrade, and Crisp is unlikely any different from any player in that regard. So what you need is for skills to make up the ground you're losing elsewhere. Whether it's his advanced baserunning (always good, but with the A's bordering on special), his reads and release in the outfield, or his approach at the plate, it appears Crisp is doing just that.

The A's are the A's, and the league's finances are the league's finances, so Crisp seems a good bet to be elsewhere on an eight-figure deal beginning in 2015, but for now, I'm completely comfortable relying on him in center field for one more year, comfortable giving the A's as reasonable a shot as ever at making the playoffs with him doing so (and with him not playing center as circumstances and his brittle body require).

Song playing as I finish: Torres, "Come to Terms."